Imagine two people witness the exact same event. They are the same age, same gender and same education. You would expect that when asked, they would give you roughly the same narrative description of the events they witnessed, right? Actually… wrong. That is totally incorrect. Their interpretation of the events will be massively influenced by their personal predispositions

A glorious and topical example brings this to life. As I write, the Houston Rockets are in a life or death struggle (probably death) with the Golden State Warriors for the NBA Western Conference Championship. Back in 2015 the Rockets were in the same position. They were in a Game 6 battle with the L.A. Clippers. This game was famous. The rockets were absolutely out of it. Down by 19 points midway through the third quarter, it was over. Their losing the game and the series was an almost mathematical certainty. Except it didn’t play out that way.

As most basketball fans remember, as a result of an astonishing final 12 minutes, the Rockets came back and won. Now, here’s the question: was this a stellar Rockets COMEBACK… or an epic Clippers COLLAPSE? Answer? Yes… depending on who you were.

I did some simple Googling of the cities’ respective local media, and how they had reported on this game – and not surprisingly, what did I find? The Houston papers, while recognizing the Clippers had allowed the door to open, focused almost exclusively on this being a heroic Rockets comeback. What did the L.A. papers report? To them, the Rockets scoring was almost incidental. To them, the story was of an epic and tragic collapse on the part of the Clippers… and what’s interesting was how the media in each market was able to make a really compelling case – USING THE EXACT SAME FACTS – to support a completely different position. Fascinating.

This is a wonderful reminder of a critical communications lesson. Just like these media outlets, your audience members will never be an intellectually neutral, blank canvas which you get to paint with your story. They come in with a whole host of “pre-existing” biases, which will significantly affect their interpretation of what you’re presenting, and consequently the outcome of your presentation. Indeed, this is precisely why so many presenters (especially in sales) walk away from a solid meeting only to learn they didn’t get what they wanted. They never knew – and therefore never addressed – the negative predispositions in the room. It’s a fatal but common mistake.

To combat this, as far as you can, you must always know what “issues, positions and interests” are held by your audience and present with these fully in mind. How do you do this?

The first piece is obvious. You have to do your research, and not just superficially. You need to know what positions the audience holds and why. For this reason, in our Message Architect software tool (MAST) the very first planning template asks you to identify your audience’s likely positions of support (tailwinds) and opposition (headwinds).

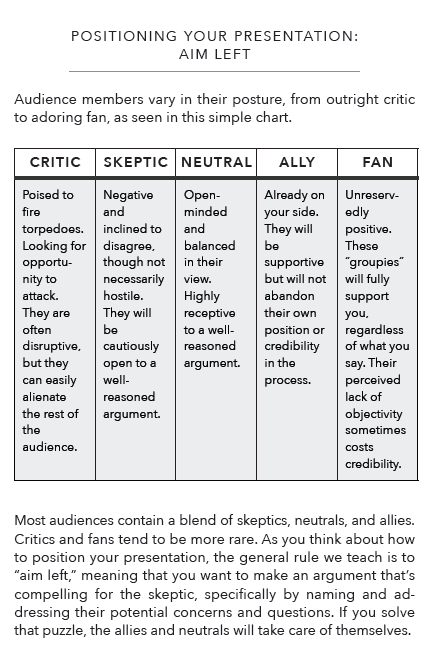

But having done this, how do you structure your message based on what you found, and especially where you found opposition? The answer to that question is very poorly understood. Let’s assume, as is usually the case, your audience is rather heterogeneous, and as such comprises 5 “types” of people as seen in the following table.

(By the way, this table, and a more in depth discussion of it, is on page 101 of my book, The Compelling Communicator.)

At which group should you target your remarks? Here’s the rule: ‘AIM SLIGHTLY LEFT’ – Why? You rarely need to speak to your own fans, because they are already going to support you. But neither is it generally wise to target the outright critics. You aren’t likely to win them over: you are more likely to prompt a potentially ugly confrontation that may turn others against you.

You should target the skeptic, by which I mean, design your argument to gently, respectfully, but deliberately turn around an uncommitted negative position, and in doing so you will also, generally, win over the neutrals. The way you do that is to develop robust insights to refute the opposition, but without being combative. Examples of such insights might be;

– “if this seems expensive – the cost of not acting is far greater than the cost of acting”

– “the team can absolutely pull this off”

– “the service failures of the past cannot happen again”

In each case you can see the objection that you’re going after. And that’s the big idea – run right at the objection.

But it all starts by understanding the example of my two basketball fans. Comeback or collapse? What you see depends on your pre-existing point of view.

Go Rockets.