In our “DeconstrucTED” series, we look at some of our favorite TED and TED-style talks. We deconstruct them to demonstrate how we all can be more effective communicators in our own right.

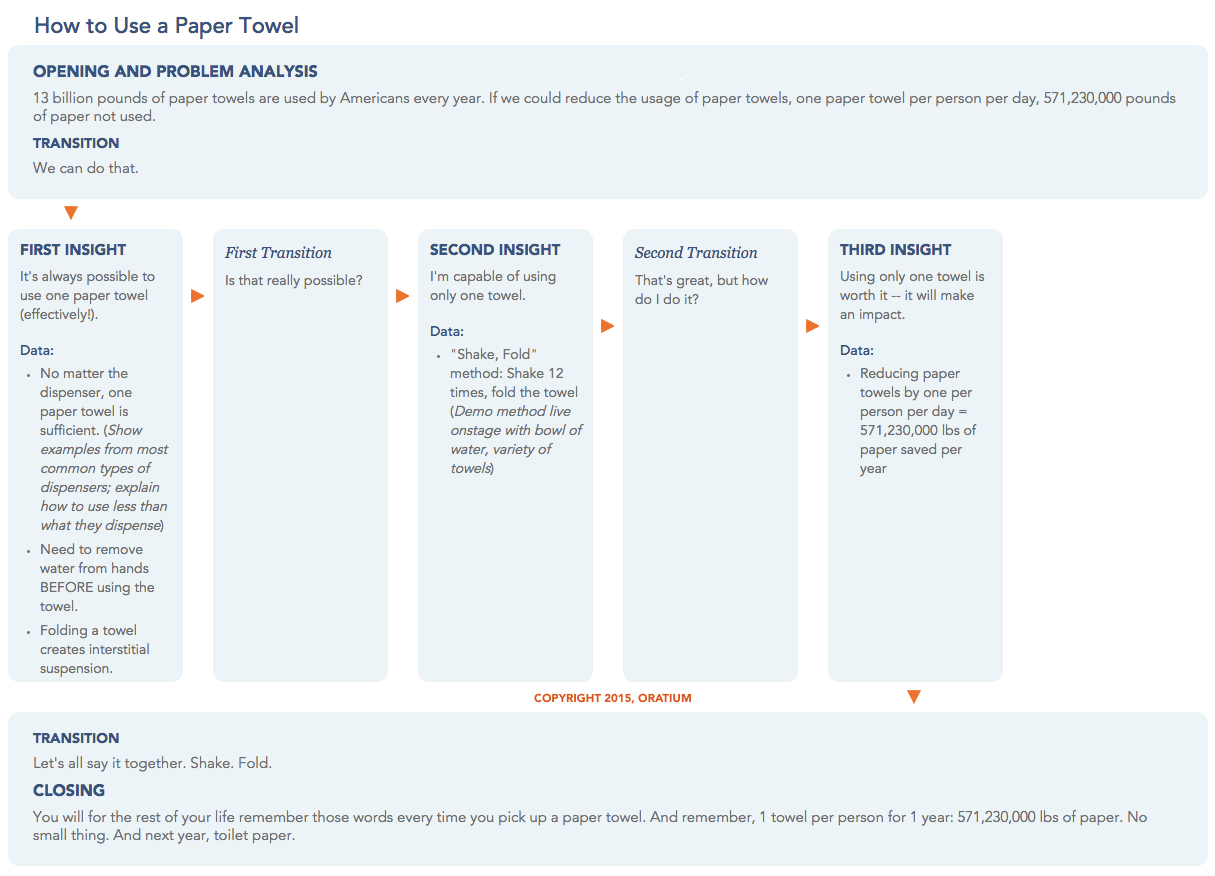

Joe Smith’s TED talk on “How to use one paper towel,” is one of Tamsen Webster’s favorites. In only 4-1/2 minutes, Joe forever changes how you’ll look at paper towels — and lands three insights while doing it.

Q: Joe Smith opens opens with a fact. Can you talk about that strategy and his opening in general?

TW: He starts with a really powerful, quick way to establish a problem that he is proposing to solve. It starts with this mammoth number about how much paper we’re using each year. A number is a great way to establish context around a problem that you’re about to solve. The danger is that it can be abstract to people, but his talk is so short that it lands under the heading of “Wow, that’s a big number” and leads into, “If we could use one paper towel per person per day, then we could reduce the amount of waste.”

This is a good way to start, given the length of the talk. To open similarly you might need to provide additional context around the number to make it more concrete.

Q: The talk is largely built around the props. To what extent would you recommend using props as an approach in a talk?

TW: The big point of his talk is how powerful demonstration can be. Demonstration has a lot of good things going for it. The brain loves visuals; it loves to see things. If there’s any way you can show people rather than tell people, then you have an advantage. You can accomplish that with a picture, or with a series of pictures where you explain what’s happening.

When you physically do this for people, you get additional benefits others wouldn’t get. First, you get the power of story because you’re watching this thing unfold as it’s happening.

The second thing is that it’s completely concrete; when you actually show someone what you’re talking about, they have no question in their minds. And because he’s showing the effect of it, he’s supporting one of those ideas that he’s trying to land.

The third thing is that the demonstration, and particularly the way he’s doing it, gets the audience involved. I use this talk to show what a good, action-oriented talk looks like. People leave thinking differently.

Q: Can you talk about how he overcame his gaffe at the beginning of the talk?

TW: Joe shows masterfully how to correct a flub. He didn’t panic, he just corrected it and he continued on. It’s a great lesson in how to handle a mistake. The audience doesn’t know something is wrong until you as the speaker say it’s wrong – and it’s the way you handle it that speaks volumes about your authority and how people continue to respond after the mistake.

The flub is minor. Everyone gets nervous. TED Talks are hard, and I don’t think people realize that there are no notes or Teleprompters. The whole talk is in someone’s head.

Q: The audience was very engaged throughout. What in particular about his style resonated with them?

TW: Oratium has identified four innate styles that people have when they speak. Joe has a style that I would describe as a “commander” style – he’s very authoritative, but not overbearing. In particular, if someone assumes the authority of being on the stage while others are in the audience, as long as the “ask” isn’t too uncomfortable or too much for people, they’ll do it.

He hits all those marks. He’s asking people to say one word, so they don’t have to remember much. He’s very clear that he’s just going to point to them as he asks them to “shake” or “fold,” making it really, really easy for them to respond. He’s also having them do it as a group, which means he’s now packing in another element of influence. It can be really uncomfortable for one person to say something in a public environment like that, but if everyone around them is also saying that thing, it becomes much easier for them to do it. Reverse engineering it, I think that’s why it’s so effective.

He made it easy for his audience to respond on a number of levels, and much of that comes from his authoritative, but authentic-feeling style.

Q: What kinds of things do you have to focus on in such a brief talk?

TW: You have to focus on critical ideas only. In any talk, you always have to answer what we call “the question in the room” – the question that naturally arises in audience member’s minds. Over the course of a talk, given what you say, everything that you say is going to raise a question; and you have to answer only those questions in a short talk. You only answer those questions that have to be answered for you to make the point that you want.

With a short talk – a talk that’s fairly simple – you have to figure out what you want people to do in order to get them to take an action you want them to take. What do they have to believe in order to do that? And what do they have to know in order to believe? In a short talk, you have to get down to only those answers – the ones that are the most critical. The way we get people to choose this info is the “Jenga test” of What can you pull out without having the tower fall over? You look at what the communication would look like without it in there. If the communication still stands, you leave it in there.

Q: What does Joe do particularly well to effectively communicate his message?

TW: He has a clear action he wants people to take. He uses the right information to land the beliefs people need to hold in order to take that action. He also does a great job of making the information really concrete.

What I really want people to take away from his talk is the power of demonstration, how effective you can be if there’s no extra information, and that it’s possible to change somebody’s mind permanently in a short amount of time if you’re really thoughtful about deciding what they need to know in order to make that change.

The reason I use this talk so much is because you cannot look at another paper towel the same way again. The reason you can’t is because he’s answered any question you might have and taken away any objection you might have about not doing the action. You may not think that reduction of paper is worth it to you and that’s fine, but he’s at least answered the question. You may not think you will actually do it, but you at least know how. And you may have started with the belief that it couldn’t be done, but – and that’s the biggest idea he had to land – you know it’s possible to do it. He totally obliterated that contrary belief. Whether or not you choose to do it, whether or not you think it’s worth it, he’s totally given you the payoff for it. It works and it’s possible. Even if people in his audience don’t change their behavior, there’s no way they can un-see the demonstration.

You watch this talk and you cannot look at a paper towel the same way. That’s the effect of any good pitch, talk or presentation.

###

Want to learn how to give a TED-style talk? Contact us to find out more about our executive speaker coaching and TED Talk-style presentation coaching.